In June, Sydney introduced water restrictions[i] amid an ongoing two-year drought in New South Wales. Authorities stated that the city was experiencing some of the lowest inflows into its catchment dams since the 1940s. At the end of the month, the City of Sydney also officially declared a climate emergency[ii], joining over 600 other local governments around the world.

With the effects of climate change becoming apparent even to the most skeptical of deniers, Australia seems headed to a situation where droughts become the new normal, not an emergency. Risk mitigation and adaptation measures are crucial for the sustainability of our societies and economic systems.

In this article, we examine some of the most notable recent water-related occurrences in Australia, the risks facing Australian companies and how they are managing them, and what investors can do to mitigate related portfolio risks.

Is the alarm justified?

Are newspapers ringing alarm bells to make headlines or are concerns justified? There is both anecdotal evidence and hard data to suggest that water scarcity issues may be underestimated.

In addition to the water restriction in Sydney, some notable occurrences in recent months include:

- The ongoing crisis of Murray-Darling River basin[iii], an area larger than Egypt, stretching 3,375 km across New South Wales, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory, as well as parts of Queensland and South Australia. The drought conditions have resulted in health warnings forcing locals to buy fresh water; over a million fish deaths[iv]; criticism of the political and regulatory failings[v]; backlash against intensive agriculture and water prices reaching AUD 650 per megalitre[vi], putting farmers under enormous pressure.

- An independent report in May 2019 asking the New South Wales government to take measures against excessive water use at two coal mines, as an investigation found mining-related water losses of up to 1.28 billion litres per annum in the state, almost double the previously predicted 690 million litres.[vii]

- Controversy around the groundwater management plan for Adani Carmichael mine. It is estimated that the mine will divert 12.5 billion litres of water from the Sutton River to the detriment of local towns and the region’s farmers. The plan was found to have serious flaws[viii], and its approval by authorities was criticized for failing to adequately consider community submissions and environmental impacts.

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows that between 2009 and 2017, the amount of water extracted from the environment and used within the Australian economy increased 19% from 64,076 gigalitres (GL) to 76,159 GL[ix]. This is equivalent to 150 times the amount of water contained in the Sydney Harbour (1GL=1 billion litres). Water consumption (i.e. not returned to the environment) increased by 23% from 13,476 GL to 16,558 GL, or about 33 times the Sydney Harbour. Most of the water is consumed by agriculture, followed by industry and households.

Over the same period GDP grew by 23% and the population by 10%, indicating that the increased rate of water consumption is not exceptional. However, the sharp increase in water use should still be of concern. The prolonged drought facing the country and the anticipated increase in water demand in the coming decades will create enormous pressure on freshwater accessibility. Therefore, decoupling human and economic growth from depletion of a vital resource like water is paramount.

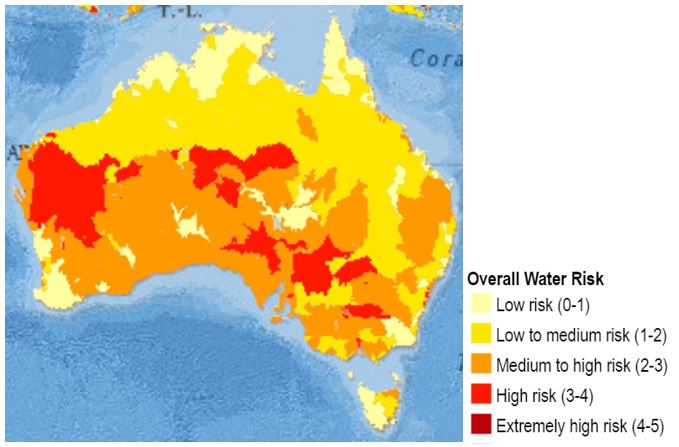

The image below, taken from the World Resources Institute’s AQUEDUCT Water Risk Atlas, shows many parts of Australia are already under significant water stress, which is projected to worsen in the coming decades, especially in the most populous urban areas. Indeed, analysis from CSIRO and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology found that there has been a decrease in streamflow across southern Australia, largely due to decline in rainfall.[x] Their future climate models also forecast a decrease in rainfall across many regions of southern Australia, with more time spent in drought. [xii]

Insights from our research

The Australian economy relies heavily on water-intensive sectors such as agriculture, energy and mining. Water can pose material risks and impacts to a company’s business and social license to operate, particularly if it operates in water-scarce regions.

Concerns over water use and availability are key drivers of community tensions, and the perception of greater water stress can make it difficult for companies to obtain water permits and project approvals. Constraints on water quality and availability may lead to higher water prices and increased production costs, disrupt or shutdown operations, or force companies to cut back production or undertake costly workarounds. Water overuse can trigger conflicts with local communities, scrutiny from regulators and negative reputational attention.

Resource Use is one of the material ESG issues in Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings framework, and addresses water-related risks. We have identified it as relevant for 64 companies in the ASX200, together representing 34% of the total market cap of the index.

Sustainalytics recently published a report outlining the results of a benchmarking exercise on water management and stewardship in the food and beverage, garment and mining sectors. The study, which included 11 Australian companies, ranked Australia among the top five regions with relatively strong preparedness. At the same time, it also found that over a two-year period only three of these companies had made progress on the assessed key performance indicators, while eight showed either no progress or deteriorated performance.

As shown in the graph below, according to our analysis on the broader sample of 64 companies, on average two thirds of the risk exposure is potentially unmanaged. Of course, values can vary considerably among companies, reflecting the variations in risk exposure and management, and therefore the probability and magnitude of the potential impacts.

Risk Decomposition

Companies have begun recognizing the risks associated with water scarcity and the strategic importance of freshwater management and conservation. Leading companies have invested in the research and development of drought-resistant crops and innovative irrigation techniques, desalination plants, and process and equipment optimizations. They may also use non-potable water for industrial processes and increase rates of water recycling and water efficiency over time. However, many of these initiatives are sporadic. Gaps remain between group-wide water risk and management programs and what we consider best practice – as evidenced by the average management score of 34 out of 100 points.

For example, 30 companies still do not publicly report basic data on their water use. Over 80% of the companies in the sample don’t provide evidence of conducting regular water risk assessments and don’t report detailed information on their water scarcity risks and their response strategies. Moreover, only seven companies have established clear managerial or board oversight on water risks and have publicly adopted water reduction targets and deadlines.

Source: Sustainalytics ESG Risk Rating

Managing water risks in portfolios

Recognition of the investment risk posed by climate change is becoming increasingly mainstream and understood, as the economic implications are little disputed and starting to be priced in. The effects of global warming are also becoming clearer, particularly around freshwater availability and stress. As described above, water-related risks can be significant and can have major impacts on companies’ operations and supply chains.

So, what can investors do to manage and mitigate water risks in their portfolios? We suggest three steps that can be useful in this regard:

- Assess the extent to which a portfolio is exposed to water risks – you can’t manage what you don’t measure. For example, modelling potential impacts of water restrictions or price hikes on investee companies can yield valuable insights.

- Understand companies’ strategies and management approaches, engage with them on the issue, and stimulate more reporting and disclosure. If there is value in such information, then a company should be reporting on it at par with other financial and non-financial disclosures – or it may fail to fulfil its disclosure duties.

- Apply the insights gathered from exposure mapping and company response: for example, by diversifying a portfolio with regards to geographic exposure and water stress, tilting portfolio allocation in terms of the water risk profile of companies and sectors, and increasing investments in companies that provide solutions to water challenges.

In our recent report, we observed evidence of a positive engagement impact, with benefits to investors and companies alike. See the full report here, and stay tuned for an upcoming blog post from Tytti Kaasinen, Associate Director of Engagement Services.

If you’re interested in learning about water-related engagement opportunities, please visit Sustainalytics’ Engagement Services website. Or learn more about the Sustainalytics solutions that can help you address water-related risks in your portfolio: