In a world where record-setting natural disasters are becoming more frequent, underwriters of property and casualty insurance have seen a notable increase in the number and size of claims in relation to these changes in climate patterns, especially in the US market.

As climate change continues to increase pay-outs to affected policyholders, it raises questions whether the standards and practices used by insurers to underwrite property and casualty policies have factored in climate risk considerations. This is amid data released by Munich Re in January 2021, where hurricanes, wildfires, and other disasters across the US caused USD 95bn in damages in 2020,1 almost double that of 2019 and the third biggest year of losses since 2010.

This loss trend affects an insurer’s financial balances and can have a deep impact on insurance business dynamics. Accordingly, as the pricing of climate change risks gets more complex, providing insurance coverage for high-risk geographical regions becomes less feasible, making it harder for policyholders to obtain adequate coverage for their properties.

Consumer Impacts

Insurance coverage against climate change risks has become a challenge in states like California, Florida, and Washington. An August 2019 report by California’s Department of Insurance found that zip codes most affected by wildfires saw a 10% jump in the number of homeowners dropped by their insurers between 2017 and 2018.2 Reconstruction after a disaster is incredibly difficult for uninsured homeowners, as is the selling of uninsurable properties; Most mortgage lenders would not grant loans without proof of property insurance; this causes depressed housing prices that affect multiple parties. The immediate impact can be seen in municipal tax revenues, which are taxed based on home sales and property valuations declining due to being in a high-risk area for climate disasters. In other instances, homeowners experience significant premium increases or are denied coverage for being in the same zip code or county of a recent disaster as underwriters respond to mounting climate change risks, significantly raising their rates or exiting certain markets.

As insurers refrain from taking on certain high-risk regions, some homeowners are relegated to state-level Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans as their last resort.3 Designed to serve a small number of high-risk consumers unable to obtain traditional policies, it is often costlier and offers less coverage than regular market plans. California reported a 225% increase in FAIR Plan fire insurance policy pool participants from 2018 to 2019, at the same time as 31% of all insurers dropping their policies.4 The state responded by enacting legislation to prevent insurers from refusing to renew policies. However, this was only a temporary measure, and it does not fully address the skyrocketing costs of providing coverage for consumers.5 California’s FAIR plan rates increased by an average of 15.6% state-wide in January 2021 (over the previous rate adjustment in 2019) in the face of mounting losses from the past couple of years.6

Government Subsidizing Climate Risks?

Over recent decades, policymakers’ decisions in the US led to a lack of recognition and ill consideration of the costs to insure physical climate risk. Examples of this include issuance of taxpayer-backed mortgage guarantees (via Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac7) for at-risk properties and relying on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) for the insurance coverage of properties on parts of the east coast that private insurers have deemed too risky and avoided underwriting.8 The lack of private market coverage for consumers has effectively offloaded the risks onto the government. As a result of underwriting approximately 95% of flood policies in the US,9 claims from more frequent natural disasters over the past few years have caused the NFIP programme to be USD 20.5bn in debt. Policies were renewed regularly despite homes being destroyed or damaged, making rebuilding in the same spots lucrative. While the NFIP’s new underwriting methodology will incorporate catastrophe modelling and is set to unveil in October 2021 (the first major change since 1968),10 it could result in significant premium surges for homeowners with higher exposures to natural disasters. In California, utilities are required to bring power to homes in centuries-old fire corridors, and the state mandates insurers renew policies at below-market rates.11 Such policies result in fragility against climate risks and discourage underwriters from entering riskier markets.

While such initiatives may prop up home values in the short term, it masks the actual costs of the risk pricing gap on properties and creates a significant drain on government budgets and come at a high cost to taxpayers. Increased physical climate risks could result in even higher losses triggering further policy price hikes that negatively impact sellers' housing values and create higher financial risks for homeowners—especially if disaster coverage was not in place.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), a standard and regulatory support organization led by chief insurance regulators in the US, published a report in November 2020 examining how insurers identify and manage their climate risks. Reviewing responses from 2018, the report found that approximately 90% of surveyed property and casualty insurers had adopted climate modelling and analytics and more than half reported on efforts to encourage policyholders and stakeholders to minimize climate impacts.12

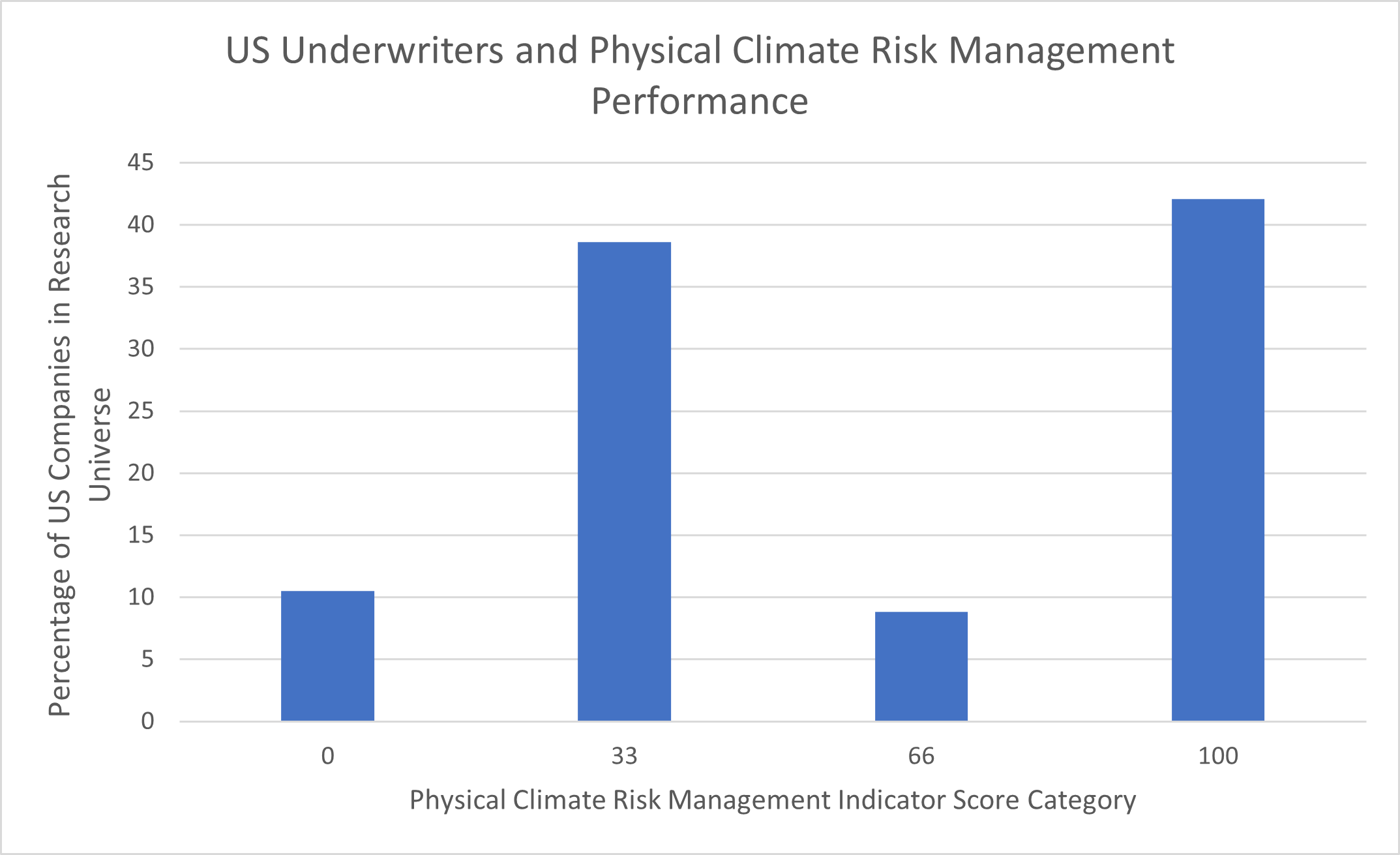

Looking at Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings universe, 57 US-based diversified insurers and property and casualty underwriters were analysed regarding their performance in “Physical Climate Risk Management”. The indicator examines an insurer’s measures to mitigate natural disaster risks in their operations, providing an indirect approach to evaluating their underwriting practices. A higher score value (out of 0, 33, 66 or 100) indicates more effective management of physical climate risks at the company.

Source: Sustainalytics

Not dissimilar to the findings of climate analytics usage rates in the NAIC survey, the chart above shows that 11% of the 57 US companies in our universe had scored a “0”, indicating no efforts to manage this issue were disclosed. Companies that score “100” on this indicator have implemented strong programs and policies, strategical integration and executive oversight on climate risk management when compared to those with lower scores. While over 40% of US companies in our research universe have achieved this score, it indicates that many underwriters still have room for improvement in their climate risk strategies to minimize policy pay-out costs.

In 2020, the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) made it mandatory for signatories to report on climate-specific indicators in alignment with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommended governance and strategy indicators.13 However, since public disclosure on this reporting is voluntary, only a fifth of signatories have made their responses public. One example of public disclosure can be found in American International Group (AIG), which outlined executive responsibilities on climate issues, its initiatives in implementing climate risk modelling and the development of sustainability-linked offerings and services.14 As greater scrutiny is placed on issuers to report on climate risks, it is anticipated that more companies will provide public disclosure on their TCFD reporting.

We anticipate that climate change will continue to cause further hardships over the next several years, especially if more intense and frequent climate events occur. Property and casualty underwriters must further integrate climate risk assessments into their underwriting criteria to accurately quantify risks to prevent sudden surges in premium costs.

The ballooning costs to insuring properties with high climate risk exposure highlights a disconnect with the true pricing of risk in the US. Between government programmes and policy decisions that do not reflect climate impacts and enable development in risky areas to insurance companies not adequately examining physical climate risk in underwriting, it resulted in a correction for which most homeowners were unprepared.

For property and casualty insurers to underwrite for at-risk homeowners while balancing financial exposure against future climate impacts, government policymakers need to consider several measures, including accurate mapping and scenario analysis of climate impacts, disaster prevention, and a gradual shift away from subsidizing climate risks. This approach can enable insurance companies to offer parametric insurance (policies that insure against specific weather events with a set pay-out amount) and help consumers better understand the severity of physical climate impacts concerning their insurance policies.

Sources:

[1] Flavelle, Christopher. “U.S. Disaster Costs Doubled in 2020, Reflecting Costs of Climate Change”. The New York Times, January 7, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/climate/2020-disaster-costs.html

[2] Flavelle, Christopher. “As Wildfires Get Worse, Insurers Pull Back From Riskiest Areas”. The New York Times, August 20, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/20/climate/fire-insurance-renewal.html

[3] Araujo, Mila. “Explanation of the FAIR Plan” The Balance, October 5, 2020. https://www.thebalance.com/fair-plan-policies-2645392

[4] Adriano, Lyle. “CA insurance regulator announces new incentives for fireproofing homes”. Insurance Business America, February 10, 2021. https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/us/news/catastrophe/ca-insurance-regulator-announces-new-incentives-for-fireproofing-homes-246123.aspx

[5] Chen, Elaine and Chiglinsky, Katherine. “Many Californians Being Left Without Homeowners Insurance Due to Wildfire Risk”. Insurance Journal, December 4, 2020. https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/west/2020/12/04/592788.htm

[6] Kasler, Dale. “‘Last resort’ insurance plan raising rates for rural California homeowners — again”. The Sacramento Bee, December 8, 2020. https://www.sacbee.com/news/california/fires/article247680725.html

[7] Colman, Zack and O’Donnell, Katy. “Borrowed time: Climate change threatens U.S. mortgage market”. Politico, June 8, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/08/borrowed-time-climate-changemortgage-market-304130

[8] Harrel, Eben. “Are We On the Verge of Another Financial Crisis?”. Harvard Business Review, December 18, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/12/are-we-on-the-verge-of-another-financial-crisis#

[9] Kaufman, Leslie. “Emergency Experts Contemplate What FEMA Should Do Next”. Bloomberg Quint, December 14, 2020. https://www.bloombergquint.com/onweb/emergency-experts-contemplate-what-fema-should-do-next

[10] Danise, Amy and Leefeldt, Ed. “FEMA’S Upcoming Changes Could Cause Flood Insurance To Soar At The Shore”. Forbes Advisor, March 18, 2021. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/homeowners-insurance/new-fema-flood-insurance-rates/

[11] Harrel, Eben. “Are We On the Verge of Another Financial Crisis?”. Harvard Business Review, December 18, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/12/are-we-on-the-verge-of-another-financial-crisis#

[12] Czajkowski, Jeffrey et al. “Assessment of and Insights from NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Data”. National Association of Insurance Commissioners, November 2020. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/cipr_insights_climate_risk_data_disclosure.pdf

[13] “Top 5 Takeaways from PRI’s First Year of Mandatory TCFD Reporting”. Manifest Climate, July 31, 2020. https://manifestclimate.com/blog/takeaways-from-pri-tcfd-reporting/

[14] “2019 Climate-Related Financial Disclosure Report”. American International Group, August 2020. https://www.aig.com/content/dam/aig/america-canada/us/documents/about-us/2019-climate-related-financial-disclosure-report.pdf